This pack includes: gp guidelines for assessment and management of cannabis use disorder, cannabis withdrawal syndrome for GPs, cannabis and mental health, key messages on cannabis, cannabis use and fertility, cannabis: what is it?

16 December 2014

Resources for general practitioners.

A resource pack for General Practitioners which includes an assessment for cannabis-related problems, the severity of dependence scale (SDS), clinician's guidelines and referral information.

Screening and managing cannabis use: comparing gp's and nurses' knowledge, beliefs, and behavior

https://ncpic.org.au/cms-data/online-catalogue/screening-and-managing-cannabis-use-comparing-gps-and-nurses-knowledge-beliefs-and-behavior/

15 January 2024

Bulletin 16

https://ncpic.org.au/professionals/publications/bulletins/bulletin-16-role-of-general-practitioners-in-provision-of-brief-interventions-for-cannabis-use-related-difficulties/

28 January 2024

4 Cannabis users in need of treatment are known to most commonly seek help from a General Practitioner (gp) or other physician.5 Importantly, however, research relating to gp-delivered cannabis use interventions is scarce.

One notable exception is an annual cross-sectional study of approximately 1,000 GPs throughout Australia which has been provided since 1998 by the Bettering the Evaluation And Care of Health (BEACH) program.6 Frewen et al.7 analysed the BEACH data between April 2000 and March 2007 and showed that GPs managed illicit drug use approximately 55,000 times per year and of these, cannabis made up 3.2 per cent of all encounters which specifie

02 March 2024

NCPIC Home Get Help Cannabis and You

Marijuana Facts - weed 101

Driving

Joint Effort

Competitions

Tools for quitting

Joint Effort

Reduce your use

Clear your vision

Parents

Parents FAQ

How to help

Free resources

Professionals

Shop

Teachers

Learning packages

Teacher's directory

Teachers Talk e-newsletter

Healthcare

gp

AOD

Tools for Quitting

Researchers

Dr Pete's commentary

Publications

2024 Conference

HR

Publications

Shop

Factsheets

Bulletins

AIC bulletins

Technical Reports

Online catalogue

ezine e-newsletter

Training

News

Weed Watch blog

Media room

Media releases

Studies

Survey results

Indigenous

Get involved

Read-along resources

Indigenous research

About Us Contact Us Copyright & disclaimor

28 January 2024

A General Practitioner (gp) is a good place to start when seeking help. A gp can help you if you are experiencing cannabis use problems either by providing treatment themselves, giving advice about available community organisations/services, or by writing a referral for an appropriate specialist (e.g. clinical psychologist). Importantly, it is often necessary to have a referral from a gp in order to receive treatment from a specialist. Not all health professionals require a referral from a gp. When you know who you w

18 December 2014

If you need some face-to-face advice close to home, your gp is a great source of information and can provide insights and advice that will help you start an effective conversation with your kids.

How to approach your teen

Talking about drugs, especially if you're worried your teen may be using, can be quite daunting. Our online or print booklet, What's the deal? Talking with a young person about cannabis, is a really useful resource to help you create a game plan for a productive conversation that doesn't cause drama.

When planning the conversation, make sure you kick it off at a place and time that is comfortable for both of you, and where you won't be cut short. Avoid the car-ride to school or just before bed, as you may have to abruptly end your discussion at a point that could leave one or both of you anxious.

Approach the conversation with an open and calm mind, and make sure you don't set ultimatums, like, 'stop using or leave the house', as you may isolate your child or cause an argument that is difficult to recover from.

If asked questions about your own past, be honest. One of the worst things that can happen is if you lie about trying cannabis in the past and get caught out. Honesty is the best basis for trust and for ongoing conversations.

Listening without judgement and encouraging questions is also a good way to show you are supportive and want to help, without building any animosity. It's also important even if your teen doesn't open up right away, as they will understand that they can approach you at a later time when they feel more comfortable.

Finally, if you feel you can't offer them the help they need, providing ideas like visiting the gp together, just to get some answers to questions, can show them you're willing to stand behind them every step of the way.

Our video series, MAKINGtheLINK Parent Program, convey

28 January 2024

Published March 2008

Anthony Arcuri, Amie Frewen, Jan Copeland, Christopher Harrison and Helena Britt

Key points

Two of every 10,000 general practice consultations involve the management of cannabis-related problems, so there is an estimated minimum of 19,000 general practice consultations in Australia for this problem annually

Compared with patients at other consultations, cannabis patients appear to be more likely to be male, to be aged between 15 and 44 years, to have a Health Care Card, and to be an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander

Compared with psychostimulant consultations, cannabis consultations appear shorter on average, more likely to involve concurrent management of psychosis and anxiety, but less likely to generate prescription of antipsychotics

There is a need to raise awareness of screening, assessment and brief interventions for cannabis-related problems among GPs to assist in early detection and more cost-effective treatment of cannabis-related problems in the community

Background

Cannabis use is infrequently managed by Australian general medical practitioners (GPs). In terms of illicit drug problems, however, it is second only to the management of heroin use, which mostly involves the prescription of opioid maintenance pharmacotherapy.1 In any given year, the majority of Australians (85%) visit a gp at least once.2 While the literature is replete with research exploring how alcohol,3 opiate,4 and tobacco5 use are managed by GPs, little is known about general practice management of cannabis use problems, particularly in Australia.

Data from the BEACH program

This bulletin explores data from the BEACH (Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health) program, which is a continuous study of general practice activity across Australia.2 This study involves an ever changing random sample of approximately 1,000 GPs per year, who each provide details of 100 consecutive consultations. The BEACH data collected between April 2000 and March 2007 (n=689,000 encounters) demonstrates that there were 129 consultations with at least one recorded cannabis problem (referred to hereafter as 'cannabis consultations'). While this represents only 0.02% of all consultations, it equates to an estimated 19,000 cannabis consultations nationally per year. This is likely to be a significant underestimate, as there were 3,650 illicit drug problems managed in this period (1 per 200 encounters) in all, but the gp did not identify the specific drug in 2,841 (77.8%) of these.

Patient and gp characteristics

The 129 specified cannabis consultations involved 105 individual GPs. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients involved in these consultations, compared with those involved in all 689,000 general practice consultations during the same seven-year period (referred to hereafter as 'general consultations'). Males appear more highly represented among patients at cannabis consultations than in the total data set, as do those aged between 15 and 44 years and those with Health Care Cards. In contrast, patients at cannabis consultations appear to involve fewer patients from non-English-speaking backgrounds than average. None of the patients at cannabis encounters were over 64 years old.

Table 1

Characteristics of patients involved in cannabis and general consultations, 2000-2007

Compared with psychostimulant consultations, cannabis consultations involved a higher proportion of patients aged 25-44 years (47.2% compared with 27.1%) and patients aged 15 to 24 years (42.5% vs. 16.4%). This differing age profile is consistent with the younger age of cannabis users reported in the general population.6 No other differences regarding patient characteristics were found. Similarly, few differences were found in relation to gp characteristics, except that cannabis consultations appeared more likely than psychostimulant consultations to be reported by female GPs (38.8% vs. 14.8%) (results not tabled).

Characteristics of cannabis consultations

The characteristics of the cannabis consultations, against the psychostimulant consultations, are set out in Table 2. Cannabis consultations were less often new problems being managed by a medical practitioner for the first time, and were most commonly claimed for government reimbursement as standard consultations (usually less than 20 minutes). Although all patients were managed for cannabis-related problems, they often presented to the consultation with other complaints, including somatic and psychological (primarily depression and anxiety) problems. Other than the management of a cannabis problem, the GPs involved in these consultations most commonly managed a physical condition (primarily digestive), followed by a psychological problem (mainly depression, psychosis or anxiety) and, to a lesser extent, another illicit or a licit substance use problem (most commonly alcohol abuse). These problems are consistent with those reported previously in research exploring the health and psychological effects of cannabis use.7-9

Table 2

Characteristics of cannabis and psychostimulant consultations, 2000-2007

Compared with psychostimulant consultations, cannabis consultations appeared less often to be long consultations (i.e. usually between 20 and 40 minutes in duration). They appeared, however, more likely to involve the concurrent management of psychosis and anxiety, neither of which was managed concurrently in psychostimulant consultations. This is in contrast to previous research showing that hospital separations in Australia for cannabis-related psychotic episodes are less common than those for methamphetamine-related psychotic episodes.10

Management of cannabis consultations

Counselling was provided by GPs for almost two thirds of cannabis problems managed. Medications were not typically prescribed for cannabis problems but, when they were, such medications most commonly included anxiolytics and antidepressants, and, in one case, a medication used for nicotine dependence. Medications prescribed for any problem during cannabis consultations included antidepressants, anxiolytics and antipsychotics. GPs referred patients for treatment of the cannabis problem in more than one in five cases, most commonly to drug and alcohol services, followed by psychiatrists and specialist medical clinics or centres.

Table 3

Management of cannabis and psychostimulant consultations, 2000-2007

Compared with psychostimulant consultations, during cannabis consultations GPs appeared to less often prescribe an antipsychotic, either for the drug problem in particular, or for any problem that was managed during the consultation. This result appears inconsistent with the previous finding that cannabis consultations were more likely than psychostimulant consultations to involve the concurrent management of psychosis. This is a neglected research question worthy of further investigation.

Conclusions

This BEACH data, spanning over seven years, shows that, despite there being around 300,000 Australians using cannabis daily,6 the number managed for this problem by GPs is very small. This is in contrast to the increasing numbers presenting to specialist AOD treatment services.11

The majority of general practice consultations during which cannabis use is managed appear to involve patients who present for problems other than their cannabis use. It seems, therefore, that many cannabis consultations involve the opportunistic management of cannabis use problems. This finding highlights the need to assist GPs to recognise high-risk groups for screening, assessment and brief intervention. Such high-risk groups may include young males, those with respiratory problems, and those with depression, symptoms of psychosis, and other mental health problems.

Furthermore, considering that the majority of GPs appear to favour treatments such as counselling in the management of cannabis use problems, and that GPs often work within limited timeframes, it follows that brief motivational interviewing may provide an effective intervention for cannabis use problems managed in general practice settings. Indeed, motivational interviewing has demonstrated efficacy across a number of health areas beyond alcohol and other drug treatment (including diet, physical activity, pain management, diabetes control, sexual behaviour, and medical adherence),12 and thus may be a broadly-applicable and cost-effective intervention for GPs.

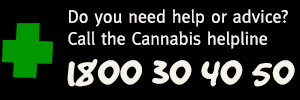

Although a small but significant minority of cannabis consultations in the current study involved the prescription of medications apparently intended to assist with cannabis withdrawal (including anxiolytics and antidepressants), the effectiveness of these or other medications for this purpose is poorly supported by research.13 Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge that, as demonstrated in the current research, sometimes cannabis use problems are complex and are associated with the management of comorbidity, including psychosis, depression and anxiety. While many patients could be referred to the National Cannabis Information and Helpline (1800 30 40 50) for assistance, in more severe and complex cases prescription of psychiatric medications and referral to specialist psychiatric and/or drug and alcohol treatment services may be required.

Limitations

For the purposes of this Bulletin, no inferential statistics were reported; therefore, the conclusions must be viewed with some caution. These data, however, will be prepared for an international peer-reviewed journal where such statistics will be reported. An upcoming NCPIC e-Zine will direct you to this paper upon its publication.

Degenhardt, L., Know, S., Barker, B., Britt, H., & Shakeshaft, A. (2005). The management of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use problems by general practitioners in Australia. Drug and Alcohol Review 24, 499-506.

Britt, H., Miller, G.C., Charles, J., Bayram, C., Pan, Y., Henderson, J., Valenti, L., O'Halloran, J., Harrison, C., & Fahridin, S. (2008). General practice activity in Australia 2006-07. General Practice Series No. 21.Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Ballesteros, J., Duffy, J.C., Querejeta, I., Arino, J., & Gonzalez-Pinto, A. (2004). Efficacy of brief interventions for hazardous drinkers in primary care: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 28, 608-618.

Strang, J., Sheridan, J., Hunt, C., Kerr, B., Gerada, C., & Pringle, M. (2005). The prescribing of methadone and other opioids to addicts: national survey of GPs in England and Wales. British Journal of General Practice 55, 444-451.

Anderson, P. & Jane-Llopis, E. (2004). How can we increase the involvement of primary health care in the treatment of tobacco dependence? A meta-analysis. Addiction 99, 299-312.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2005). 2004 National Drug Strategy Household Survey: Detailed Findings. Canberra: AIHW.

Hall, W., Degenhardt, L. & Lynskey, M. (2001). The health and psychological effects of cannabis use. Monograph Series No. 44. 2nd ed. Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing.

Copeland, J., Gerber, S. & Swift, W. (2006). Evidence-based answers to cannabis questions: a review of the literature. ANCD Research Paper 11. Canberra: Australian National Council on Drugs.

McLaren, J. & Mattick, R.P. (2007). Cannabis use in Australia: Use, supply, harms, and responses. NDARC Monograph No. 57. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre.

Degenhardt, L., Roxbrugh, A. & McKetin, R. (2007). Hospital separations for cannabis- and methamphetamine-related psychotic episodes in Australia. Medical Journal of Australia 186, 342-345.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2007). Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia 2005-06: Report on the National Minimum Data Set. (Drug Treatment Series Number 7). Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Resnicow, K., DiIorio, C. & Soet, J.E. (2002). Motivational interviewing in medical and public health settings. In: Miller, W.R. & Rollnick, S. (eds). Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press, 251-269.

Haney, M. (2005). The marijuana withdrawal syndrome: Diagnosis and treatment. Current Psychiatry Reports 7, 360-366.

28 January 2024

Using cannabis can have unpredictable effects.

Some of the unwanted physical and psychological effects that may be experienced by a person when they are ‘high’ on cannabis may include:

nausea and vomiting

anxiety, panic and paranoia

If you are with someone who is affected by cannabis in this way, you can help.

What can you do if someone is physically sick?

‘Greening out’ is a term that refers to the situation where people feel sick after smoking cannabis. People can go pale and sweaty, feel dizzy, nauseous and may even start vomiting. They usually feel they have to lie down straight away.

You can assist them by:

taking them to a quiet place with fresh air

sitting them in a comfortable position

giving them a glass of water or something sweet (such as juice or a piece of fruit)

If the person feels so sick that they start to vomit:

stay with them

lie them down on their side, not on their back, so they don't choke on their vomit

keep them in a quiet, safe spot where you can monitor them

If someone is physically sick it is important that you never leave them on their own, not even for the shortest time. Suffocating on vomit is a very real threat and can lead to an otherwise unnecessary death.

What can you do if someone is experiencing panic attacks, anxiety or paranoia?

Unwanted psychological effects can range from depression to anxiety, which can go on to produce panic attacks and paranoia. Although this can be frightening for the person, most of the time these effects can be managed through reassurance.

If someone you know experiences these problems after they have used cannabis, here are some things you can do to assist them:

try to calm the person down

reassure them that these feelings will pass in time

take them to a safe and quiet place and stay with them

let them know that you are here to help them. If there is something you can do for them, do it

if they do not calm down, try to distract them with other topics of discussion

If nothing you do is helping

If there is nothing you can do, and the person continues to feel bad or their condition gets worse, then it is important to get more help. Call 000 or take them to get medical help so that they can be treated quickly and safely.

How can you help prevent this from happening again?

After the effects of cannabis wear off, talk to your friend about what happened, how it affected you and those around you, and how this can be prevented in the future.

As a friend, you can do the following things that may help prevent this happening again:

if your friend has a mental illness such as depression, anxiety or schizophrenia, encourage them not to use cannabis or any other drug, unless prescribed by a doctor

encourage your friend to seek help from their gp or counsellor about their cannabis use if this happens regularly

remind them what happened the last time they used cannabis

suggest they avoid bingeing or polydrug use (using more than one drug at the same time), or anything that will intensify the effects of cannabis

become involved in other activities with them that do not involve drug use

For more information please see the NCPIC fast facts booklet 'concerned about someone's cannabis use? Fast facts on how to help'.

Factsheet published June 1, 2008. Updated October 1, 2011.

06 March 2024

Is there such a thing as cannabis withdrawal?

For much of the 1960s and 1970s, researchers did not consider cannabis to be a drug of dependence due to the lack of a withdrawal syndrome similar to that seen with opioids or alcohol. Many carefully controlled animal and human research trials, however, now clearly demonstrate that a withdrawal syndrome occurs when regular cannabis smokers stop smoking.

Cannabis withdrawal is similar to the withdrawal experienced from stopping tobacco smoking. As with tobacco, the withdrawal symptoms associated with cannabis can be disruptive enough to contribute to continued use and also contribute to relapse in people trying to quit. Cannabis withdrawal is not the same for everybody. Various factors influence the severity of cannabis withdrawal. Factors that may influence how severe cannabis withdrawal will be and how long it may last when someone tries to quit are:

how much cannabis the person uses (people who use cannabis frequently will have a more severe withdrawal)

how dependent someone is (people who are more dependent upon cannabis are likely to have a more severe withdrawal

how sensitive a person is to distress (people who are are less tolerant of emotional distress may experience a more pronounced cannabis withdrawal syndrome)

Most studies suggest that withdrawal symptoms start on the first day of abstinence, and usually peak within the first two to three days of quitting, with the exception of sleep disturbance. In general, withdrawal symptoms are usually over after two weeks, but this depends on how dependent someone is on cannabis before trying to quit.

What are the symptoms of cannabis withdrawal?

When people stop using cannabis after prolonged use (either because they cannot get any or because they are trying to quit) they may experience a variety of withdrawal symptoms including:

sleep difficulties including insomnia and strange dreams

mood swings/irritability

depression

anxiety/nervousness

restlessness/physical tension

reduced appetite

nausea

cravings to smoke cannabis

Whilst individual symptoms can be relatively mild, in combination they can still contribute to why a person keeps using cannabis and why they may relapse if trying to quit.

Is there any treatment for cannabis withdrawal?

Some people may find that they need a counsellor to help them manage their cannabis withdrawal symptoms and prevent relapse. Other people may be able to manage the symptoms on their own. Getting a good night’s sleep may be one of the most important factors for ensuring success. This may be difficult since sleep disturbance is one of the most common withdrawal symptoms, although it does not make it impossible. Practising good ‘sleep hygiene’ can help someone to manage the sleep difficulties associated with withdrawal. This involves such things as not drinking caffeine after noon, exercising daily especially in the morning, having a comfortable bed, avoiding alcohol or other drugs to help you sleep, and avoiding stimulating activities before bed (like playing video games). Developing a good plan for combating sleep disturbance can make it easier to cope with the other withdrawal symptoms.

Simply recognising and being aware of the mild but important effects of cannabis withdrawal symptoms can help someone to successfully reduce their use or quit. Studies have shown that the chances of successfully quitting cannabis are greatly increased once the intense phases of withdrawal have passed– so it is important to developing a coping plan before trying to quit.

If someone continues to feel discomfort after two weeks of abstinence from cannabis, it may be related to the underlying reasons for using cannabis in the first place (such as anxiety, depression or social issues). In these cases, people trying to quit may want to seek the help of a gp or counsellor to discuss strategies to deal with these underlying issues. Rebates may be available through Medicare or private health insurers for services provided. As yet, there are no effective pharmacological treatments to help reduce cannabis withdrawal symptoms or to block the effects of cannabis, although studies are underway. There are a handful of studies that demonstrate that brief cognitive-behavioural treatments can be helpful for people trying to abstain or reduce their cannabis use.

For more information please see the factsheets 'cannabis and dependance' and 'treatment for cannabis use problems'.

Factsheet published November 1, 2011.

26 March 2024

At our National Cannabis Helpline (1800 30 40 50), we often get calls from parents or caregivers who are concerned about their child’s cannabis use and the effects it is having on their lives. They call wanting advice on the usual things like how they can have a conversation with them about their use; how they can help the person they care about to quit or reduce their use, and how they can get up-to-date information about cannabis and its effects. Their primary focus is usually on how they can help their child or loved one, and much less often, on what effect their child or family member’s use is having on them.

Help! I’m at my wits end – my child is addicted to cannabis

Although it’s not a conscious thought many parents have, because they are so concerned about their child, it is important to think about how you are coping. How are you dealing with the constant strain of being a parent or a caregiver to someone with cannabis use issues? Your ‘child’, who may be still living with you, could be over the age of 18, so maybe you feel like you’ve got limited authority to tell them how to act or what to do. Perhaps you’ve already had the conversation with your child (many times) about how cannabis might be negatively affecting them, and how you really, really want them to quit. Maybe you’ve already researched methods and services to help your child quit, and suggested to them in both subtle and not so subtle ways that they should access these services. But your child just isn’t interested. They just don’t want to quit smoking weed, or they feel they can’t. So nothing changes.

In these situations, it’s really important, as a parent or caregiver, you move into self-care mode. It doesn’t mean you’re not there for your child, but you need to prioritise your own health and wellbeing, in addition to trying to help them.

How to look after yourself: create a Self-Care Plan

One of the best things you can do to protect your own wellbeing is to create a plan of what you’ll do and who you’ll turn to when it all gets too much. A kind of ‘Self-Care Plan’. Create a list of trusted friends and family members (who don’t live with you), who you can talk with whenever you feel overwhelmed. It’s important you choose people you feel comfortable talking to about your child’s cannabis use problems, who won’t judge you or cause you to feel embarrassed. Perhaps let health professionals who you regularly see, like your gp, know about the problems you’re experiencing, so there is someone who’s aware of what’s happening if you need to reach out to them.

Also, make a list of the types of activities that help you de-stress. Maybe it’s yoga, going for a walk, taking a long hot bath, spending time with your dog, getting a massage or working on a jigsaw puzzle. Whatever works for you. So when you need to let go of some steam, you’ve got some ideas about what works best for you.

How to look after yourself when you feel physically threatened

While it is often stated in the media that weed is the drug of peace and harmony, many family and loved ones know this is not necessarily the case – especially when cannabis users are intentionally or unintentionally in withdrawal. If you feel like your physical safety may ever be compromised by the behaviour of your child or loved one, it’s good to know what you’ll do in that situation as well. Many parents would be extremely reluctant to call the police if they ever felt threatened by their child’s behaviour, especially when drugs may be involved. As a parent you don’t want to see your child arrested by the police and receive a possible criminal record or jail time. You just want to ensure your own safety and that of the rest of the family. In this case, add to your list of people to reach out to, the name of someone who is physically strong and you feel confident would be able to come around to your house and physically handle the situation in a calm and confident manner, without inflaming the situation.

No one wants to have a child who is addicted to cannabis and can’t seem to help themselves. It’s a very stressful situation. While it is good to do everything you can to help them, you also need to look after yourself and make sure you’re prioritising self-care and care for other vulnerable family members in this difficult situation.

For more information on how to help as a parent, check out our Parents FAQs page, or download our brochure Concerned about someone’s cannabis use? Fast facts on how to help. You can also call the great people at our Cannabis Helpline on 1800 30 40 50 for a chat, to vent, or for some advice.

Bulletin 22

https://ncpic.org.au/professionals/publications/bulletins/bulletin-22-pharmacy-based-interventions/

26 March 2024

John Howard, Jan Copeland, Peter Gates, Morag Millington, Denis Leahy and Carlene SmithNational Cannabis Prevention and Information CentreThe Pharmacy Guild of Australia (New South Wales Branch)

Potential harms associated with cannabis use

Cannabis is the most commonly used illicit drug in the Western world. Despite this, the effects of cannabis use and dependence on mental and physical health and psycho-social functioning are typically under-recognised and under-treated.1 This represents missed opportunities for health promotion and brief and early interventions for those who are already experiencing cannabis use-related difficulties.

People’s personal experience with cannabis use, including those in the health workforce, can influence opinions on the health impact of cannabis use. Opinions based on personal experience often ignore significant changes in the patterns of cannabis use over the past 30 to 40 years. These include differences in the frequency and quantity of cannabis use, a significant decline in the age of initiation of use, an increase in potency of the cannabis plant, and use of the more potent parts of the plant.1, 2, 3

There is increasing evidence of an association between cannabis use and cognitive impairment in attention, memory, and the organisation and integration of complex information.3 As cannabis is usually smoked, there are risks for respiratory disease, such as chronic bronchitis. In addition, most smokers mix cannabis with tobacco and are also regular tobacco smokers. There is evidence that some of the negative respiratory effects of cannabis and tobacco may be additive. This concurrent cannabis and tobacco use may complicate the management of smoking cessation, particularly if the treatment seeker wishes to abstain from only one substance. That is, cannabis use may prompt relapse to tobacco use and vice versa.4

Early onset, frequent and heavy use of cannabis exacerbates mental health conditions, including schizophrenia, manifesting as increased symptoms and severity, non-compliance with treatment and more frequent hospitalisations.5, 6

Role for Pharmacists

Pharmacists represent a unique position in healthcare, and are particularly relied on to provide healthcare where medical practitioner availability is limited. A study by Dhital7 has outlined how ‘pharmacy reform’ aims to provide patients with better choices and access to healthcare through the utilization of pharmacists’ skills and expertise. She notes that this is most evident in areas such as self-care, management of long-term conditions, the delivery of public health messages and improving access to services. In particular, pharmacists can be trained to deliver brief interventions during medication reviews with cannabis users and provide advice to those recently diagnosed with a health condition where smoking cessation would be beneficial, and for pregnant customers. Early work suggests that typical pharmacist visitors are positive about brief interventions for alcohol use, and view pharmacies as informal places where no appointment is required.7 This was particularly the case where pharmacies have a consultation room.

Screening and brief intervention practices may have, on average, only small effects, however, they require minimal training and can be cost-effective.8 Pharmacists are in a position to deliver such interventions using an ‘Ask, Advise, Refer’ approach. Notably, there is emerging evidence that pharmacists can be effective in providing information, screening, brief interventions and referrals in relation to tobacco smoking and problematic alcohol use. Although pharmacists support playing a role in addressing concerns in these two areas, a number of barriers prevent this from being enacted. That is, many believe they lack the required skills and resources, have negative attitudes towards people dependent on alcohol, tobacco and/or other drugs, lack confidence in the efficacy of pharmacy-based and brief interventions, and were concerned there would be no remuneration for their efforts.7, 9, 10 In addition, a study in New Zealand and England11 revealed that pharmacists had concerns about offending or alienating customers and invading their privacy. Finally, as pharmacists may lack the knowledge and confidence to provide brief interventions, the importance of promoting ‘role adequacy’ was noted in a study from Scotland.12

In relation to interventions focussed on tobacco use, a systematic review noted that individuals who work in pharmacies (including pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, dispensary assistants, and trained staff) have regular interactions with large numbers of people who may benefit from drug-related screening and intervention. This review supported the effectiveness of the delivery of non-pharmacological tobacco use cessation interventions (including offering behavioural counselling or support), as well as those combining non-pharmacological interventions with pharmacological approaches.3

While research to date has focussed on two licit drugs – nicotine and alcohol, pharmacists are extensively involved in opioid substitution treatment, including the provision of methadone, buprenorphine, buprenorphine and naloxone in combination (Suboxone) and other medications, and have a role in extending needle and syringe availability. However, little is known about the potential role of pharmacists in relation to the use of cannabis.

The Project

The National Cannabis Prevention and Information Centre (NCPIC) and the Pharmacy Guild of Australia (NSW Branch), have been working together to explore the potential role of pharmacists in health promotion and delivering brief, opportunistic interventions in relation to the cannabis use of their customers.

It is not proposed that the pharmacist takes on a clinical counselling or therapy role, but rather one of a concerned healthcare provider, who can assist a customer’s consideration of their use of cannabis and its health and broader implications, and provide them with evidence-based information and referral guidance where appropriate. Importantly, the brief, opportunistic interventions that are proposed meet the requirements under the 5th Community Pharmacy Agreement (2010-2015) with the Australian Government, in relation to the provision of health promotion and brief clinical interventions.

The project builds on a similar National Cannabis Prevention and Information Centre (NCPIC) project with general practitioners. It aims to expand the dissemination of evidence-informed information on cannabis and the potential risks associated with its use (particularly mental and physical health issues), teach appropriate interventions (brief or otherwise) and provide referral information. The project comprises both research and practice components.

The research component

The research component had two parts – (i) qualitative and (ii) quantitative.

A qualitative study with 11 pharmacists explored their views and attitudes towards cannabis and cannabis users and any perceived barriers to providing brief intervention. There was broad support for the provision of information and brief interventions, and questions raised about engagement with customers who could benefit, in conjunction with realities of pharmacies. The results were used to develop the quantitative instrument and the process for recruiting pharmacists and pharmacy staff to complete the survey.

For the quantitative study, the online survey went ‘live’ in mid February 2013. The survey used was modelled on the NCPIC survey of general practitioners and Sheridan’s (2008) survey of pharmacists’ views on providing expanded services related to alcohol use-related difficulties. Specifically, this survey gathered information on the attitudes of pharmacists to cannabis and its use; their potential role in health promotion and provision of brief, opportunistic interventions (ie information provision, health promotion, clinical advice and referral) and their willingness to do them; any barriers to such provision; and resources that could assist. The invitation to complete the survey was circulated via email to NSW Pharmacy Guild members, and a wider pharmacy audience including pharmacy interns.

The online survey was completed by 129 pharmacists and the data from this sample is discussed. Despite widespread advertisement, the sample size is small, and this may reflect the contested views about the role of pharmacists in provision of screening and interventions addressing illicit substance use.

These participants were aged 22 to 71 years (M=45.6, SD=12.5), and almost two thirds were male (61%). Participants worked in metropolitan (49%), regional (24%), and rural and remote areas (27%), and had worked an average of 23 years (SD=13.4) as a pharmacist.

The majority (77%) of respondents believed pharmacists could be effective in providing brief, opportunistic interventions to cannabis users, and 60% believed that screening alone can lead to a positive change. However, over half (56%) rated their knowledge about cannabis as poor to very poor and only 39% rated it as acceptable to strong. Additionally, 73% rated their skill-level in screening for cannabis use-related difficulties as poor to very poor.

A scale representing the participants’ belief that treatment can help cannabis users comprised four items, each scored from one-to-five, where higher scores show stronger belief (5 =‘I can help’). This scale had adequate internal consistency for a four item scale (α=0.65).

Table 1: Pharmacists’ attitudes on cannabis treatment utility

Agree

Neutral (%)

Disagree (%)

Conducting a 10 minute brief intervention of someone’s cannabis use can lead to positive change

50.4

27.6

22.0

Effective psychological treatments exist for helping people reduce their cannabis use

46.4

36.8

16.8

Effective pharmacological treatments exist for assisting with cannabis withdrawal

41.0

34.6

24.4

People in my position can be effective in assisting customers with their cannabis use

81.1

13.4

5.5

A second scale was created to indicate a participants’ role importance in providing a treatment (12 items, each scored from one to five where higher scores show less perceived importance (5 = ‘I am no help’). This scale had good internal consistency (α=0.80).

Table 2: Pharmacists’ attitudes to their role importance in cannabis-related screening or intervention*

Mean score (0-4)

SD

Most people who use cannabis do not need intervention

3.1

1.3

Customers may not be receptive to it

3.9

1.1

I do not have time

2.9

1.2

I do not have the skills

3.6

1.3

I do not have personal interest

2.3

1.2

I do not have professional interest

2.1

1.1

I do not have support from colleagues/organisation

2.9

1.3

Cannabis users should only be treated by specialists

2.9

1.2

Cannabis use is often not the most important issue

2.9

1.1

I do not want to attract more cannabis users to the pharmacy

2.5

1.3

The effort required is not justified

2.6

1.2

Cannabis users are unpleasant to work with

2.3

1.2

Total role importance scale score

33.9/60

8.0

(*higher score reflects stronger agreement)

The participants reported an average belief in treatment score of 14.0 out of 20 (SD=2.7), and an average role importance score of 33.9 out of 60 (SD=8.0).

Participant gender, age and location of their pharmacy were not significantly associated with these scale scores.

Pharmacy experience

The participants had worked up to 48 years as pharmacists (M=23.0, SD=13.4), and reported spending up to 82 hours per week in their pharmacy, with an average of 36.6 (SD=14.5) hours.

The vast majority (93%) of participants reported offering customers tobacco smoking cessation advice and had provided clinical interventions which met the requirements under the 5th Community Pharmacy Agreement (2010-2015). Despite this, the sample was not likely to have reported screening more than one customer for cannabis use in the past month (M=0.7, SD=4.6; 9.3% screened at least one), and were not likely to have provided any brief interventions (M=0.5, SD=2.0; 16.3% provided at least one), referred any cannabis-using customers to a drug and alcohol clinic (M=0.3, SD=1.3; 10.9% referred at least one) or mental health service (M=0.2, SD=0.5; 11.6% referred at least one).

No indicator of pharmacy experience was significantly associated with the belief in treatment or role importance scales.

Cannabis training, knowledge and beliefs

Just under half the participants (48.1%) reported at least a small amount of cannabis-related training and only one in ten (10.9%) reported having received a moderate or substantial amount of training. For those who did report at least a small amount of training (47%), under one third (29.5%) reported that this training had been delivered within the past two years.

More than half of the sample (55.5%) reported that their cannabis-related knowledge was poor or very poor and only one in twenty (5.2%) reported strong or very strong knowledge. An even greater proportion (72.6%) reported poor or very poor skills in screening for cannabis problems, with only 3.2% reporting strong or very strong screening skills. In addition, 100% of the sample agreed that they should receive education about cannabis. In order to feel more confident in screening for cannabis use, the participants suggested that they should receive more training (93.8%), access to up-to-date intervention guidelines (85.3%), more options for referral (73.6%), more resources (72.9%), and the belief that screening leads to positive outcomes (60.5%).

Some of the participants’ (44.2%) believed that cannabis should be available for medicinal purposes or available as a maintenance therapy in a pharmaceutical preparation (46.5%). This was more common than those who believed cannabis should remain illegal (34.9%), or be decriminalised (28.7%).

The variation in participant scores on the belief in treatment and role importance scales was not significantly associated with any variation in responses to these indicators of cannabis-related training, knowledge or beliefs.

Cannabis harms

The participants reported that an average of 6% (SD=8.0) of their customers would be at least weekly cannabis users, and believed that an average of 32.2% (SD=29.8) of those who try cannabis would someday develop cannabis dependence; three times greater than expected. This later belief was significantly associated with role importance (R2=0.12, B=0.09, t=3.72, p

The majority (89.9%) of participants commonly agreed that cannabis users were more likely to have a mental health concern than non-users and 83.6% disagreed that it is OK to smoke cannabis as long as it does not become a habit. In addition, 77.8% of the sample commonly agreed that cannabis withdrawal can act as a barrier when quitting cannabis. The sample was likely to indicate agreement that cannabis-related harms were similar to alcohol-related harms (59.1%) but responded with mixed agreement to the idea these harms were similar to tobacco-related harms (52.8% agreed, 41.8% disagreed, 5.5% neutral)

The variation in participant scores on the belief in treatment and role importance scales was not significantly associated with any variation in the proportion of participants who agreed or disagreed with these harm-related beliefs.

Beliefs regarding participant treatment seeking

The sample believed that, if someone was concerned about their cannabis use, they would first seek help from a general practitioner (gp) (M=5.7, SD=2.2) or counsellor (M=5.0, SD=1.9). Other common responses included: a pharmacist (M=4.9, SD=1.9), an alcohol or other drug treatment service (M=4.8, 2.5), online support (M=4.6, SD=2.4), or a friend (M=4.2, SD=2.5). The sample was less likely to believe that a cannabis user would seek help from a support group (M=3.6, SD=1.9) or from a self-help workbook (M=3.3, SD=2.0).

The variation in participant scores on the belief in treatment and role importance scales was not significantly associated with any variation in the proportion of the sample sharing each of these beliefs.

The views of pharmacists participating in this study are comparable to those of the general public. The National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing14 reported that among those with cannabis dependence seeking help, a gp is the most common form of treatment (12% of males and 25% of females) followed by a psychiatrist (4% of males and 6% of females) or psychologist (3% of males, 8% of females). In addition, according the National Minimum Data Set15 cannabis users most commonly receive counselling (43%) followed by withdrawal management (13%). Treatment settings are typically non-residential (70%). In an unpublished online survey of 500 regular cannabis users conducted by NCPIC, the order of treatment seeking was: GPs (43%), counsellors (24%), self-help books (12%), internet (10%), support groups (9%) and an alcohol or other drug facility (2%). Pharmacists were a little more likely to believe that more cannabis treatment seekers would go to a drug or alcohol treatment service than actually do.

Conclusions from the survey

Notwithstanding the small sample, the study indicates that there does exist a willingness among a section of pharmacists to become equipped to raise the awareness of customers of possible health concerns that could arise from cannabis use, and to provide screening, information, brief interventions and referrals to customers who may be experiencing cannabis use-related health concerns, or who are considering a reduction or cessation of their cannabis use. Essentially, the findings are identical to previous studies of pharmacists’ opinions regarding the screening and brief intervention for alcohol and tobacco use.8-13 That is, they believed that they required more information on cannabis, its use, health impacts and broader implications, and capacity building to raise their skill level and confidence. The activities described below have been undertaken to address these concerns.

Practice component

In order to address the knowledge gaps identified in the study, NCPIC and the Pharmacy Guild of Australia (NSW Branch) have produced a Cannabis Kit for Pharmacists to use in community settings, which builds on a similar one for general practitioners. Selected NCPIC Factsheets were adapted for use by pharmacists and their customers. These, together with the Severity of Dependence Scale and various NCPIC resources, form the package for use by pharmacists in community settings. Some content from the package appears in the Appendices, and the kit is available to download at: https://ncpic.org.au/workforce/pharmacists/

Capacity building workshops have been provided at Pharmacy Guild conventions to demonstrate how pharmacists could engage with customers who may have cannabis use-related difficulties, in addition to evening workshops in selected areas of NSW. The NSW Branch is piloting the cannabis information package with pharmacists who have indicated a willingness to be involved.

The content of the Cannabis Kit for Pharmacists includes:

Screening and intervention flow chart (see Appendix 1)

Motivational enhancement for pharmacists with cannabis users: ‘5 key questions’ (see Appendix 2)

Referral information.

Factsheets for customers (5) and pharmacists (10) on: cannabis, potency, dependence, withdrawal, pregnancy, mental health, prescribed medications, driving, the law, synthetic cannabis and treatment.

NCPIC booklets: Fast facts series on: cannabis, how to help someone and mental health; What’s the deal? series on: quitting, facts for young people, facts for parents and talking with a young person about cannabis.

Severity of Dependence Scale.

Treatment guidelines.

Clearing the smoke DVD.

Project Members

NCPIC: Dr John Howard, Professor Jan Copeland and Morag Millington.

Project Collaborators

Denis Leahy and Carlene Smith, Pharmacy Guild of Australia (NSW Branch); Associate Professor Timothy Chen, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Sydney; Associate Professor Janie Sheridan, research director and deputy head of school, School of Pharmacy, University of Auckland; and Jennie Houseman, consultant pharmacist, Community gp & Pharmacy Liaison, Northern Sydney Area Drug and Alcohol Services, NSW Health.

References

1. Copeland, J. & Howard, J. (2012). Cannabis use disorder. In: Rosner, R. (eds) Clinical Handbook of Adolescent Addiction. Chichester: Wiley and Sons.

2. Copeland, J., Rooke, S., & Swift, W. (2013). Changes in cannabis use among young people: impact on mental health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 26, 325-329.

3. McLaren, J. & Mattick, R. (2007). Cannabis in Australia: use, supply, harms and responses. Monograph Series No. 57. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre.

4. Budney, A.J., Vandrey, R. G., Hughes, J. R., Thostenson, J. D., & Bursac, Z. (2008). Comparison of cannabis and tobacco withdrawal: severity and contribution to relapse. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 35, 362-368.

5. Kuepper, R., van Os, J., Lieb, R., Wittchen, H., Höfler, M., & Henquet, C. (2011). Continued cannabis use and risk of incidence and persistence of psychotic symptoms: 10 year follow-up cohort study. British Medical Journal 342, d738.

6. Large, M. (2011). Cannabis use and earlier onset of psychosis: a systematic meta-analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry 68, 555-561.

7. Dhital, R. (2007). Alcohol screening and brief intervention by community pharmacists: benefits and communication methods. Journal of Communication in Healthcare 1, 20-31.

8. Strang, J., Barbor, T., Caulkins, J., Fischer, B., Foxcroft, D., & Humphreys, K. (2012) Drug policy and the public good: evidence for effective interventions. Lancet 397, 71-83.

9. Dhital, R., Whittlesea, C., Norman, I., & Milligan, P. (2010). Community pharmacy service users’ views and perceptions of alcohol screening and brief interventions. Drug and Alcohol Review 29, 596-602.

10. Sheridan, J., Wheeler, A., Chen, L., Huang, A., Leung, I., & Tien, K. (2008). Screening and brief interventions for alcohol: attitudes, knowledge and experience of community pharmacists in Auckland, New Zealand. Drug and Alcohol Review 27, 380-387.

11. Horsfield, E., Sheridan, J., & Anderson, C. (2011). What do community pharmacists think about undertaking screening and brief intervention with problem drinkers? Results of a qualitative study in New Zealand and England. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 19, 192-200.

12. McCraig, D., Fitzgerald, N., & Stewart, D. (2011). Provision of advice on alcohol use in community pharmacy: a cross-sectional survey of pharmacists’ practice, knowledge, views and confidence. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 19, 171-178.

13. Mdege, N. & Chindove, S. (2014). Effectiveness of tobacco use cessation interventions delivered by pharmacy personnel: a systematic review. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 10, 21-44.

14. Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2008). 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: summary of results. Canberra: ABS. Available: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4326.0

15. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2013). Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia 2011-12. Drug treatment series 21. Cat No HSE 139. Canberra: AIHW.

06 March 2024

The link between the use of cannabis and mental health problems is an issue that receives a great deal of attention in the research and general media. Although severe illnesses such as schizophrenia have received a large portion of this attention, there is also debate about whether the use of cannabis can lead to more common psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety.

There have been a number of studies that have explored the link between cannabis use and mental health symptoms. Strong associations are often found but this is not the same as a causal link (i.e. one causes the other).

Psychoses refers to a group of mental illnesses where people experience difficulty in distinguishing what is real and what is not real. Someone suffering from a psychosis might hear voices or see/taste/smell things that are not really there (hallucinations), or have beliefs that are not true (delusions). Hallucinations and delusions are usually accompanied by confused thinking and speech, making it difficult for other people to understand the person and for the person to function in life. Schizophrenia is the best known of the group and is one type of psychosis.

There have been reports of people experiencing psychotic symptoms after smoking a lot of cannabis or more cannabis than they are used to. This is called drug-induced psychosis. It is uncommon and the symptoms, although frightening at the time, go away when cannabis use is stopped.

Does smoking cannabis cause schizophrenia?

Evidence suggests that using cannabis may trigger schizophrenia in those who are already at risk of developing the disorder, and they may experience psychosis earlier. Any use of cannabis can double the risk of schizophrenia in those who are vulnerable, and bring on a first episode up to two and a half years earlier. Use of cannabis at a young age and heavy use of cannabis are associated with up to six times the risk for schizophrenia; especially smoking three or more times per week before the age of fifteen. Those with a vulnerability to developing schizophrenia, such as having a family history of the illness, should be strongly advised against using cannabis for this reason. Cannabis has been clearly shown to make psychotic symptoms worse in people who already have a psychotic disorder such as schizophrenia. People with existing psychotic disorders should be strongly advised and assisted to cut-down and/or cease their cannabis use.

Does smoking cannabis cause depression or anxiety?

The link between cannabis and other more common mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety is confusing, because cannabis is also often used to relieve symptoms of these conditions.

Although some people say the use of cannabis alleviates their symptoms of depression, there is evidence that smoking cannabis may make depression worse. People who use cannabis have been shown to have higher levels of depression and depressive symptoms than those who do not use cannabis. There is growing evidence to suggest that cannabis use, particularly frequent or heavy use, predicts depression later in life. Young women appear to be more likely to experience this effect.

Cannabis can lead to symptoms of anxiety, such as panic, in the short-term, which a fifth of users experience, but there is a lack of evidence pointing to cannabis as an important risk factor for chronic anxiety disorders such as panic disorder or obsessive compulsive disorder.

Are some people more at risk than others?

Generally speaking, people who start smoking cannabis at a younger age (early adolescence) and smoke heavily are more likely to experience negative consequences. This may in turn lead to mental health problems, but may also lead to more general life problems, like conflict at home or school/work, financial problems and memory problems.

Importantly, if someone has a genetic vulnerability (i.e. close family with depression, psychosis, bipolar disorder or anxiety) or has an existing mental health issue, cannabis should be avoided.

What help is available?

A good place to start is to visit your gp who can work with you to develop a mental health care plan. Rebates for services provided by healthcare professionals may be available through Medicare or your private health insurer. Psychologists, occupational therapists, social workers and nurses may have specific training to provide therapy or counselling for people with cannabis and mental health problems.

The doctor can refer you to either drug and alcohol services and/or mental health services which are available in most areas of Australia. Ideally they will use a coordinated approach that will tackle both issues at the same time. Treatment usually involves counselling and in some cases medicine is prescribed to assist with symptoms of mental health problems. This should be managed by a general practitioner (with specialist training if possible) or a psychiatrist.

Adis Telephone Support

Australian Capital Territory

(02) 6207 9977

New South Wales

(02) 9361 8000 1800 442 599

Northern Territory

(02) 8922 8399 1800 131 350

Queensland

(02) 8922 8399 1800 131 350

Australian Capital Territory

(02) 6207 9977

New South Wales

(02) 9361 8000 1800 442 599

Northern Territory

(02) 9361 8000 1800 442 599

Northern Territory

(02) 9361 8000 1800 442 599

Northern Territory

(02) 9361 8000 1800 442 599

Northern Territory

(02) 9361 8000 1800 442 599

Jurisdiction(Year of Indication)

Maximum amount ofCannabis allowed

Exclusion

Fine

Alternatives topaying fine

SA (1987)

100n grams plant material

20 grams resin

1 plant

Artificial cultivation:Cannabis oil

$50-$150

Criminal convition

SA (1987)

25 grams plant material

2 plants

Artificial cultivation:Cannabis oil

$100

Criminal convition

SA (1987)

25 grams plant material

2 plants

$200

Criminal convition

Online Support

National Cannabis and Prevention Information Center

ncpic.org.au

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit. Laboriosam voluptas ipsum accusamus fuga voluptatibus esse aliquam cumque error, perferendis ducimus sunt voluptatum praesentium quam debitis eius dolore maiores ex tenetur!

Reduce your use

ncpic.org.au

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit. Laboriosam voluptas ipsum accusamus fuga volupta quam debitis eius dolore maiores ex tenetur!

National Cannabis and Prevention Information Center

ncpic.org.au

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit. Laboriosam voluptas ipsum accusamus fuga volupta quam debitis eius dolore maiores ex tenetur!

Reduce your use

ncpic.org.au

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit. Laboriosam voluptas ipsum accusamus fuga volupta quam debitis eius dolore maiores ex tenetur!Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit. Laboriosam voluptas ipsum accusamus fuga volupta quam debitis eius dolore maiores ex tenetur!

Reduce your use

ncpic.org.au

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit. Laboriosam voluptas ipsum accusamus fuga volupta quam debitis eius dolore maiores ex tenetur!Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit. Laboriosam voluptas ipsum accusamus fuga volupta quam debitis eius dolore maiores ex tenetur!

Reduce your use

ncpic.org.au

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit. Laboriosam voluptas ipsum accusamus fuga volupta quam debitis eius dolore maiores ex tenetur!Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit. Laboriosam voluptas ipsum accusamus fuga volupta quam debitis eius dolore maiores ex tenetur!

Reduce your use

ncpic.org.au

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit. Laboriosam voluptas ipsum accusamus fuga volupta quam debitis eius dolore maiores ex tenetur!Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit. Laboriosam voluptas ipsum accusamus fuga volupta quam debitis eius dolore maiores ex tenetur!

Factsheet published June 1, 2008. Updated June 1, 2012.

28 January 2024

A gp or counsellor can help develop a mental health care plan to coordinate treatment. Rebates for services provided by health professionals such as nurses, GPs, psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers and occupational therapists may be available though Medicare and private health insurers.

In addition to face-to-face psychological interventions, programs based on CBT and motivational enhancement approaches are available through the internet and telephone. These programs contain many of the same facets as face-to-face treatment and offer their own advantages and disadvantages.

NCPIC has developed two treatment programs for those unable or unwilling to attend face-to-face consultations due to issues such as geographical isolation, transport difficulties, work committments or the stigma they may feel about attending an alcohol and other drug treatment facility. These programs are the web-based Reduce Your Use and the telephone-based treatment offered by the Cannabis Information and Helpline.Reduce Your Use is a web-based treatment program to help people cut down or quit their cannabis use.

Some of the advantages of using a web-based treatment, such as Reduce Your Use include:

research indicates that online programs, including Reduce Your Use, can assist people who want to quit or reduce their substance use

the treatment is highly convenient as it can be used at any location that has Internet service at the time of the user’s choice

the treatment is free

for people who feel uncomfortable about seeking treatment, this concern is reduced because the treatment is delivered without face-to-face contact, and the user is able to be anonymous. Further, the user does not have to talk to an actual person, so can feel free and comfortable to be completely open

while the program is automated, it is also highly interactive, with personalised feedback provided to the user. The automation offers the advantage of treatment being consistently delivered in the manner intended

the user can go through the program as many times as he or she likes

no doctor’s referral is required to receive the treatment

The limitations of using a web-based treatment, such as Reduce Your Use, for cannabis use may include:

it can be harder to maintain motivation using an online treatment program. Hence, it is much more common for people doing a program online (versus in-person) not to complete the entire program

while the program provides the user with personalised feedback, it can never be as personally tailored as in-person or telephone-delivered treatments

research suggests that Reduce Your Use and other web-based programs may not be as efficacious as in-person treatment

online programs provide a lower level of social support than do in-person treatments

To start using Reduce Your Use, click here: https://reduceyouruse.org.au/

The advantages of using a telephone-based treatment, such as the Cannabis Information and Helpline include the following:

research indicates that telephone-based interventions can assist individuals in reducing cannabis dependence severity and cannabis use problems to a greater extent than no treatment and to a similar extent to face-to-face interventions

individuals using the telephone may feel their personal space is less threatened compared to the encroachments of waiting rooms and a professional’s office. In addition, there is relatively less opportunity for the individual to experience stigmatisation that may be associated with illicit drug use or treatment seeking

frequent contact with other cannabis users can decrease one’s motivation to reduce their use and increase the chance of relapse in those who have quit—receiving treatment via the telephone will not increase one’s access to other cannabis users

the treatment can be delivered free at a time between 11am and 8pm on weekdays from any location that can receive a te

28 January 2024

Group One: What do you know about cannabis? Separating fact from fiction!

a) Start with a ‘brainstorm’ about what three things they ‘know’ about cannabis

b) Correct information

c) Short quiz:

The strength of cannabis has increased dramatically over time

Cannabis can only be detected in urine up to 4-8 days even with heavy levels of use

Some cannabis users experience serious mental health problems

Cannabis use does not have any serious physical health consequences

Cannabis use by the mother during pregnancy does not harm the unborn child

d) Brainstorm ‘correct’ answers, use PowerPoint presentations (PPTs), and provide information as necessary (PPTs 6-32)

e) Focus remainder of session on pulling information together

Close

Resources needed:

Poster-style information charts:

Show available diagrams/illustrations that show the effect of cannabis on the brain and other body systems

PPTs 1-32

Group Two: Helpful messages for mates/mob

a) Start with showing NCPIC posters and stories – actual posters and on PPTs 34-50:

Cannabis and sport

Cannabis and driving

Cannabis and control

Cannabis and friendships

‘Cannabis – it's not our culture’ posters done by young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – Thursday Island, Lockhart River, Griffith and Kintore (Michael Tjangala Gallagher), and one by adult women – Jubullum

b) Elicit feedback on the posters:

Is the message clear?

Does the picture tell a story?

What do you think of the colours used?

c) Read stories from the selected posters – elicit feedback and discuss

d) Participants develop their own message and poster on the theme ‘Cannabis and Culture’

e) Display posters and share stories

Close

Resources needed:

NCPIC posters: cannabis and sport, cannabis and driving, cannabis and control, cannabis and friendships, ‘Cannabis – it's not our culture’ posters done by young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – Thursday Island, Lockhart River, Griffith, Kintore (Michael Tjangala Gallagher), and Jubullum

Stories from the posters

Art materials (Textas and drawing pads)

PPTs 33-52

Group Three: Reducing harms

a) Start with a ‘brainstorm’ about what is ‘harm’

b) Discuss and correct any misinformation

c) Questions:

What information are you going to take back?

How can you help a mate who might have a problem with cannabis?

Suggestions:

if your friend has a mental illness like depression, anxiety or schizophrenia, encourage them not to use cannabis or any other drug, unless prescribed by a doctor

encourage your friend to seek help from their gp or a counsellor about their cannabis use if they experience mental health problems

remind them of any negative effects from cannabis use they may have experienced

suggest they avoid bingeing or polydrug use, or anything that will intensify the effects of cannabis

become involved with other activities with them that do not involve drug use

d) Play selections from CD – what are the messages in the songs?

e) Can they do better? Generate lyrics for ‘HR Rap’

Pull sessions together and close

Group Four: Tidy up – An optional session

a) Start with a ‘brainstorm’ about what three things they now ‘know’ about cannabis

b) Questions:

So, what do you think people your age who use cannabis like about it – get from it?

What do you think they might like less about it – lose from using cannabis?

If someone your age was using too much cannabis, what good things might they achieve from giving up or reducing their use?

What might make it hard for them to give up or reduce their use?

c) Summarise

d) Brainstorm ideas for spreading the messages….. and try to encourage some commitment from participants to try some of these when they return to their peer groups.

e) Focus remainder of session on pulling information together

Close

Resources needed:

Copy of ‘Clear your vision’ booklet

PPTs 59-61

Case Study: Mudyi Yindyamarra (respectful mates) – ‘Young Men and Yarndi’ Aboriginal youth camp with Lithgow students

In collaboration with the Lithgow Information and Neighbourhood Centre (LINC), a not-for-profit community-based organisation, NCPIC supported a youth camp in Yarramundi, NSW, with young Aboriginal men from Lithgow. The three-day camp provided seven students who identified as Aboriginal, ranging from the ages of 12-15, with education on culture, health and lifestyle, with a specific focus on cannabis-related issues. Prior to the camp, a cannabis information session was organised by Sonia Cox from LINC for elders, community members and mentors which was co-facilitated with Dr John Howard and Dion Alperstein.

Owen Smith, Jim Lord and Heath Zorz, all Wiradjuri men, Dean Murray an Aboriginal Community Liaison Officer from the Department of Education and Dion Alperstein, a NCPIC staff member, were mentors for the student participants. Each day was structured around physical team-building activities such as canoeing, abseiling and rock climbing, with educational sessions scheduled between activities. Aboriginal community members and camp mentors Owen Smith, Jim Lord, Heath Zorz and Dean Murray actively involved the young people in discussion about their culture, which many of the boys knew very little about. While there were no formal ‘cultural education sessions’, cultural discussions were often raised, more often than not during meals when all the students were seated together. The timetable and structure of the camp is outlined below.

Education about cannabis-related issues was based around five key themes; frequency of cannabis use by young people; changes in potency; cannabis and the foetus; cannabis in urine; and cannabis and mental health.

On Day One, participants brainstormed in groups and decided upon the three things they knew about cannabis. This was then presented to the group and they were provided with the correct information or an explanation of their facts if they were unsure about anything. Following this, each student filled out a quiz in order to assess what participants already knew about cannabis and its effects. After the quiz the participants were provided with information around the five core themes and other relevant cannabis-related issues (supported by PowerPoint slides). In general, the young men were very interested in the information and came up with a number of cannabis-related questions as a result. The young men were particularly attentive when discussing harm reduction strategies, such as not holding your breath for a long time when smoking. During this session a number of common misconceptions about cannabis and cannabis use were addressed and when some of the young men raised incorrect information, this too was corrected.

On Day Two, the participants discussed as a group, what they believed the risks were in using cannabis. Participants were then shown a number of NCPIC posters, each of which had a short description attached. Posters had messages about cannabis and sport, driving, control, friendships and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture. After showing the young people the posters and reading out the stories, they were asked whether the messages were clear and whether the pictures told a story. A group discussion was based around these two questions. Participants were then instructed to create posters that conveyed their own messages. After the posters were completed, each participant explained their poster and story to the group.

Finally, on Day Three, participants split into groups and discussed the impact of cannabis on their lives and in their communities. Participants were then played a number of songs from the winners of the 2010 NCPIC Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Music Competition and asked to discuss the messages in the songs. Participants then discussed the impact of cannabis on their lives and communities and wrote lyrics to their own song/hip-hop rap. Each group was given the opportunity to perform or read the lyrics to their rap and the participants discussed what they liked about each group’s song. Particular attention was paid to the meanings of each rap and the impacts/harms cannabis has on their lives and communities.

At the end of this session an informal conversation was initiated that summed up the five key themes regarding cannabis-related issues and asked the students what they learnt and how they would use this information when they returned home. The participants were also asked what they could do to help a family member or friend who might have a problem with cannabis.Pre- and post-cannabis knowledge based on the five identified key themes around cannabis-related issues were determined. The camp participants improved their knowledge by 34 per cent, initially scoring 46 per cent before the camp and 80 per cent at the end of the camp on the questionnaire.

At the Follow-up BBQ participants were asked to reflect on the camp as a whole, the information they retained, and whether they had passed any of it on to family or peers. They also completed the knowledge quiz for the third time. They had previously completed the quiz at the start of the camp and at the end. Scores on the third completion of the quiz that took place at this BBQ, five months after the camp, showed that participants had retained all of their knowledge.

In relation to key messages, the young participants recalled the risks of using bucket and plastic bongs, and the possible contaminants in cannabis. However, they did not mention potential mental health harms and those that could impact on a safe and healthy pregnancy. They said that they could and would, if the situation arose, pass on information they held to both family members and peers, and that they would adapt to the audience. In particular, they said they would be more likely to encourage quitting cannabis use altogether, given the negative health effects as opposed to simply providing harm minimisation tips. They indicated that they felt equipped to attempt to discourage family members and/or peers from initiating use of cannabis, and provide cautions on the potential harms to current users.

The participants were also asked about the camp itself, and they indicated that about 10 to 15 participants would be the ideal number. They said that a mix of young people who did and did not use cannabis should create no difficulties that they could foresee. The possibility of similar camps for young Indigenous women was welcomed. They believed that young women would be more likely to spread the messages learnt at the camp via social media, as opposed to talking amongst family and peers. In relation to the ratio of activities to information, the young participants believed that the balance was right.

They did not endorse the suggestion of information on sexual and reproductive health, as they believed these issues were covered well enough at school and other venues. Likewise, they felt that any ‘special’ attention to ‘culture’ would not be positively received, and that just because they were ‘Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander’ did not mean that they had to be constantly exposed to ‘cultural activities’. They did, however, welcome the possibility of informal conversations that led to stories of the past and their people, and current predicaments.

Inclusion of issues related to tobacco use was welcomed, as they understood the links between the use of tobacco and that of cannabis. It was felt that the link could be ideally explored via the messages around holding smoke in the lungs and potential harms that could accrue. This could also be extended to the inhalation of petrol and other volatile substances.

It might also be possible to include exposure to the NCPIC ‘Clear Your Vision’ website and resource, to alert participants to the existence of the site, how it can be used, and how they may introduce the site to their peers.

In addition, information was received from teachers who said that the young participants spoke very enthusiastically and positively about the camp to school staff as well as other students. Similar positive feedback was received from some members of the families of the young participants.